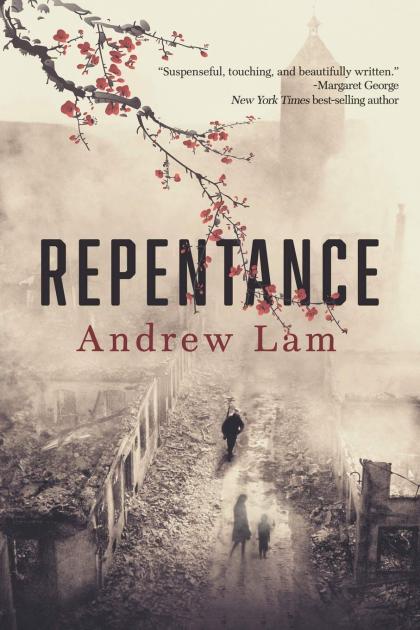

Repentance, by Andrew Lam

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

“The fact that they had nothing to do with Pearl Harbor didn’t matter. They were guilty by association, by the color of their skin and the slant of their eyes. It didn’t matter that they didn’t speak Japanese, or that they were American citizens. The bottom line was that their kind had perpetrated a horrid crime that came from the land of their ancestors. The shame was a burden that all Nisei silently bore, a burden every soldier in the 442nd was fighting to be free of.”

I got this book for free as a win from LibraryThing’s Early Reviewers program. Thanks!

“Repentance” tells the story of Daniel Tokunaga, a successful surgeon, who is confronted with his estranged father’s past during the Second World War. Daniel’s father is of Japanese descent and fought as part of the 442nd Infantry Regiment, the most decorated unit in U.S. military history.

During (mostly) alternating chapters narrating of 1944 (Daniel’s father and his best friend) and 1998 till 1999 we learn a lot about Daniel and his own family as well.

Even though Lam doesn’t have his own style, his writing is fairly well, at times very atmospheric and – in the respective context – mostly absolutely plausible and believable. Lam’s prose at times feels even poetic:

“The house sucked up his voice, offered no return. […] The house was a time capsule. A grave, he thought. Even a clock’s tick would have been welcome music. The dead room gave Daniel the creeps. Inside, the distant pulsation of the cicadas felt far away. Inside, time had died—life gone elsewhere. Even the past had passed on.”

Especially the war time perspective is brilliantly developed and I found ourselves immersed in the narration:

“The horror of their situation now dawned on Ray. Unable to advance, unable to retreat, six guys left against four machine guns, one of which they couldn’t see but which could see them the minute they lifted their heads or stepped out from behind a tree.”

Why then only three stars? There are two issues with this book: First of all, “Repentance” is missing the chance to tell the story of the 442nd – why did it become the most decorated unit? Why did those Nisei fight so valiantly? Lam could have elaborated on this beyond the rather simplistic direct answer he gives himself:

“The fact that they had nothing to do with Pearl Harbor didn’t matter. They were guilty by association, by the color of their skin and the slant of their eyes. It didn’t matter that they didn’t speak Japanese, or that they were American citizens. The bottom line was that their kind had perpetrated a horrid crime that came from the land of their ancestors. The shame was a burden that all Nisei silently bore, a burden every soldier in the 442nd was fighting to be free of.”

Especially in the light of Americans of Japanese descent being held in civilian internment under harsh conditions, why would people volunteer to fight and die for the country that did that to them? The book leaves us without even trying to explain that.

The story “Repentance” tells us is a powerful one and it would certainly have been possible to highlight the special challenges that the Nisei faced in the USA before, during and – in part at least – after World War II. I for one would have been interested to learn more about that.

In the author’s “Historical Notes” there is indeed additional information about the 442nd but it comes too late (it should have been interwoven in the story) and it’s too little to make any great difference.

The second issue I have is with Daniel, the protagonist, himself: When he learns about a family secret his father, Ray, has kept, Daniel is very, very quick to condemn Ray. No doubt, under the specific circumstances Daniel is sad and confused and he says so:

“He closed his eyes and exhaled deeply. “I still can’t wrap my head around the stuff with my dad. It’s just so bizarre.””

That is wholly understandable and believable. Nevertheless, he completely condemns his father and is generally awfully quick to judge:

“No wonder his father hadn’t wanted the government to investigate his medal. Because he hadn’t earned it…worse, he’d lied […]”

Not quite the next second but at most hours later, he clearly identifies with his father again:

“Celeste, I would love to tell you about my dad. I’m very proud of him.”

Daniel actually “oscillates” between blaming his father for everything gone wrong in both their lives and blaming himself. Both with equal vigour and both implausibly quickly, often in the course of hours:

“As Daniel perused his dad’s archive of his life, he felt a deep sense of regret. Was it my fault for keeping us apart all those years? Was it me who robbed both him and my children of a relationship they could have shared? And Daniel realized, it was.”

“No, Daniel”, I want to shout, “it’s at most partly your fault but mostly your father who tried to mould you into the unrealistic picture he imagined someone else would have been having of you.” (Yes, the convoluted wording has a very good reason.)

In the relationship between the parent and a child, it’s extremely rarely the child to blame for the major failures.

Neither is it possible for anyone burdened like Daniel to follow his wife’s – Beth – trivial advice:

“You can do it differently. Start right now. Just start by being a person who’s not carrying a burden. Now that we know where that burden came from, why don’t you put it down and leave it there?”

No, Beth, you can’t just put such a burden down and move on. If things were so easy, a lot of shrinks would be out of a job.

All in all, “Repentance”, in spite of the shortcomings I mentioned, is a well-written, interesting book that could have achieved more but can still be recommended to anyone with an interest in historical fiction and especially those interested in World War II.

View all my reviews