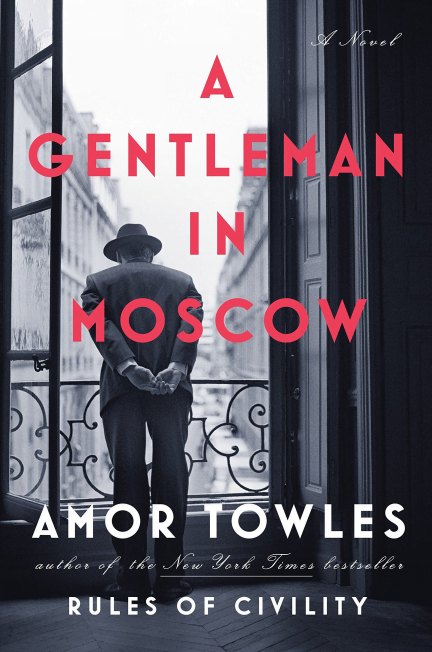

A Gentleman in Moscow, by Amor Towles

A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor Towles

My rating: 1 of 5 stars

“It was suddenly as if the book were not a dining room table at all, but a sort of Sahara. And having emptied his canteen, the Count would soon be crawling across its sentences with the peak of each hard-won page revealing but another page beyond. . . .”

This book was a huge let-down. Amazon tells me, its print edition has 378 pages. Those must be metres high and wide because I swear it were 10.000 for me. In fact, reading this book felt exactly like my opening quote.

Count Alexander Rostov has the bad luck to be born into a family of aristocrats during revolutionary times. His only redeeming feature from the perspective of his “comrades” is a poem he wrote. Which is why they don’t put him against a wall but into life-long house arrest inside his favourite hotel, the Metropol in Moscow. Ok, well, he’s moved from his favourite suite to the attic but ultimately, Alexander makes the very best of it or – as the blurb puts it – “can a life without luxury be the richest of all?”

The answer, sadly, is no. A resounding “no” because the Count – being a self-declared “gentleman” lives after a code of honour that more reliably imprisons him than any government ever could. He reads what he’s supposed to read (Montaigne, but in his most brutish way he uses the book to prop up his table! Oh heaven, what a villainous miscreant!), lives where they tell him and lives out a quaint live which, to be honest, is simply immensely boring.

During his first year of house arrest Rostov meets Nina who is (metaphorically) going to become his daughter’s mother. Their meeting is amusing and their adventures raised my hopes for a good book but, alas, it was not to be. Nina becomes first a pioneer, next an exile and ultimately a victim of her Soviet dream and we only ever get reminiscences about her. An opportunity lost.

Now, the Count gets settled into a life that’s the very definition of twee and is actually happy with it. He meets a beautiful (willowy) woman whom he “consorts with” but would never risk his modest but gentlemanly bachelorhood for her. Not even “moving together” in the hotel ever crosses his mind.

He twists a young girl whom he calls his daughter into a younger version of himself whom he basically (and gentlemanly!) has to “push from the nest” because she’s afraid of the world beyond the doors of her hotel home. Which is mostly the Count’s very own fault.

Here’s an example so you can make your own mid up – it’s pretty much the best example of the strenuous way of telling a non-story:

“After all, what can a first impression tell us about someone we’ve just met for a minute in the lobby of a hotel? For that matter, what can a first impression tell us about anyone? Why, no more than a chord can tell us about Beethoven, or a brushstroke about Botticelli. By their very nature, human beings are so capricious, so complex, so delightfully contradictory, that they deserve not only our consideration, but our reconsideration—and our unwavering determination to withhold our opinion until we have engaged with them in every possible setting at every possible hour.”

Why, yes, I haven’t made that up – he did it!

Even worse, the characters don’t develop in any way. The Count at 32 (at the beginning of the book) feels pretty much exactly the same (namely like a wise old sage!) in all aspects that matter (yes, he takes one step after another but that’s not what I mean) compared to himself at 64 (at the end of the book). His friends are the same as well; they’re all noble, self-deprecating and revere “His Excellency”, the Count without ever criticising or questioning him.

We don’t learn much about “Russia under[going] decades of tumultuous upheaval”; in fact such small matters as World War II are mostly skipped or “charmingly” referred to. All that ever matters is the count, the willow and his daughter.

Only during a few key moments in the book do we get to see real emotions and passions. If and when we do, though, it certainly “shakes the dust from the chandeliers.”. Because one thing’s for sure: Towles can definitely write. Let’s take a look at Rostov remembering something as simple as bread:

“The first thing that struck him was actually the black bread. For when was the last time he had even eaten it? If asked outright, he would have been embarrassed to admit. Tasting of dark rye and darker molasses, it was a perfect complement to a cup of coffee. And the honey? What an extraordinary contrast it provided. If the bread was somehow earthen, brown, and brooding, the honey was sunlit, golden, and gay. But there was another dimension to it. . . . An elusive, yet familiar element . . . A grace note hidden beneath, or behind, or within the sensation of sweetness.”

An author who can so richly and evocatively write on such a simple subject most certainly deserves my respect but the story is so lacking it’s the book’s ruin. Whenever passions run high, we really get to see the quality of writing but there is way too much of what I like to call “non-content” – filling material, literary waste products – that gather and celebrate dark masses in honour of their ilk:

“For the record, the Count had risen shortly after seven. Having completed fifteen squats and fifteen stretches, having enjoyed his coffee, biscuit, and a piece of fruit (today a tangerine), having bathed, shaved, and dressed, he kissed Sofia on the forehead and departed from their bedroom with the intention of reading the papers in his favorite lobby chair. Descending one flight, he exited the belfry and traversed the hall to the main stair, as was his habit.”

For the record, I know the Count to be a slave of his habits and I really couldn’t care less (especially in such detail!) about the exact measure of his eccentrics.

Said eccentricities lie not only within the Count but inside the author as well and once fancy strikes (he’d probably prefer the less prosaic “providence”) him it’s “as if Life itself has summoned them” (the eccentricities!) and force him to randomly capitalise words. Must be the literary adoption of wagging one’s finger, I guess.

It’s truly sad because the book has an interesting premise and the potential for greatness which it can’t fully realise despite having something to say:

“I have had countless reasons to be proud of you; and certainly one of the greatest was the night of the Conservatory competition. But the moment I felt that pride was not when you and Anna brought home news of your victory. It was earlier in the evening, when I watched you heading out the hotel’s doors on your way to the hall. For what matters in life is not whether we receive a round of applause; what matters is whether we have the courage to venture forth despite the uncertainty of acclaim.”

Only the ending – amusingly exactly the piece most proponents of this book loathe – somewhat reconciles me – the Count finally overcomes his artificial convictions and starts living a little, next to a willow…

A satisfying end to a book that seemed to never end but eventually came to a proper close.

Amor Towles writes like I would imagine Count Knigge on a charming rampage.

View all my reviews