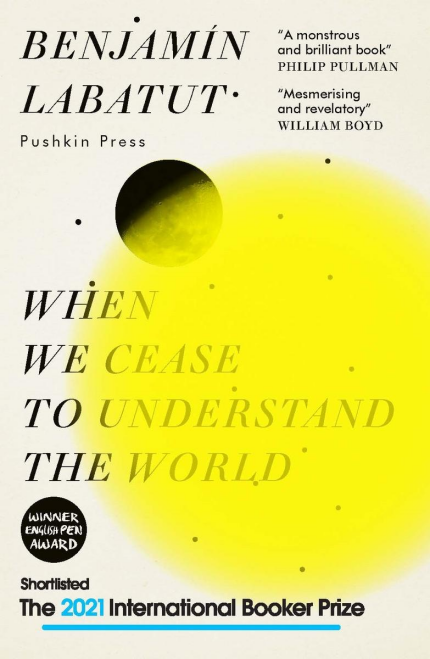

When We Cease to Understand the World, by Benjamín Labatut

When We Cease to Understand the World by Benjamín Labatut

My rating: 1 of 5 stars

This is one of the very few books I’m not finishing. Let me explain why: The problem with this one is that Benjamín Labatut introduces the history of an invention to us. Let’s take the first story on “Prussian Blue” as an example:

Labatut starts by shortly describing the invention itself and what lead to it. He then proceeds to tell us about the inventor(s) and how they relate to each other and the world. Labatut does this, and that’s my first issue, at break-neck speed. He drops name after name after name and forms connections between them in rarely more than a single sentence. It’s exhausting and not very illuminating.

Much worse, though, whenever there’s insufficient historical evidence Labatut chooses the most lurid and raciest possible explanation. For example Fritz Haber’s (Haber played a most prominent role in chemical warfare) wife, Clara Immerwahr, did commit suicide – but the reasons are unclear. Immerwahr’s marriage to Haber was unhappy on many levels and she may or may not have been against World War I – there are conflicting accounts.

Labatut, though, decides to paint her as condemning Haber for perverting chemistry and killing herself about that.

If there are two possible conclusions, it’s always the sensationalist one Labatut chooses. Even in that first story, in which the author claims is only one fictionalised paragraph, there are a lot of instances in which Labatut takes great liberty at recounting the details of his subject.

Last but not least, I do not like the ambivalent form: Labatut writes as if presenting established historicals facts but on the other hand takes literary freedom especially in later stories without clearly marking such occasions – what’s true and what’s his artistic license? Unless you take the time and actually research the subject matter yourself, you won’t know. And you’ll never know at which points Labatut overly simplifies the facts or goes on to embellish them.

»The quantity of fiction grows throughout the book; whereas “Prussian Blue” contains only one fictional paragraph, I have taken greater liberties in the subsequent texts, while still trying to remain faithful to the scientific concepts discussed in each of them.«

This book isn’t really about scientific concepts, though, but about the societal and historical implications of those concepts and how they influenced their inventors and the world. That – without embellishments and fictionalised parts – could be a truly interesting read.

The way this book is written, though, is just a wild, high-speed ride through selective and partly fictionalised history. That’s not for me.

One star out of five.

Ceterum censeo Putin esse delendam

View all my reviews